An amputation tent set up at camp.

An amputation tent set up at camp.

The Civil War has been romanticized and re-enacted for years. This subject captures the imagination of scholars and history buffs alike. The amount of information available is mind-boggling. The American Civil War had the most photographic coverage of any conflict of the 19th century and set the stage for the development of future wartime photojournalism.

For the first time, people at home could read the papers and follow the triumphs and devastations. The coverage came complete with grisly photos of their men dying on the battlefields. Photographers like Matthew Brady, Alexander Garner and Timothy O’Sullivan to name a few lived among these soldiers. Their beautiful, heart-breaking photographs show documented proof that war is indeed hell.

In the 1860’s medical care was extremely limited. While today broken bones and cuts are rarely life threatening, during the Civil War this was not the case. In battle, soldiers were very likely to be seriously wounded at such close combat. Back at camp, disease and poor hygienic conditions were just as likely to cause serious illness or death. Basically, a soldier’s life was a double-edged sword and the Grim Reaper was his ever-present guest. The photojournalists were there to document it all.

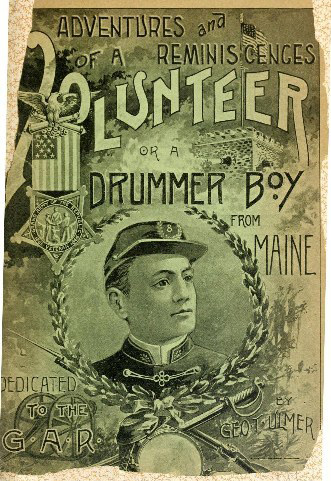

In my previous post, I wrote about George’s unlucky friend the Drummer Boy from Pennsylvania. After that soul crushing morning,George was given the assignment to assist in the surgeon’s tent.

These makeshift field hospitals were a dismal place with little hope. Surgeons were basically butchers, sawing off arms and legs that had been shot or stabbed in order to save the soldier from gangrene and other infection. To the left is a photo of a box of surgeon’s tools used at these battlefield medical tents. Just looking at it makes me squeamish. I can’t imagine how a 15 year old boy far from home could find the strength to perform the gruesome task he describes in his memoirs:

These makeshift field hospitals were a dismal place with little hope. Surgeons were basically butchers, sawing off arms and legs that had been shot or stabbed in order to save the soldier from gangrene and other infection. To the left is a photo of a box of surgeon’s tools used at these battlefield medical tents. Just looking at it makes me squeamish. I can’t imagine how a 15 year old boy far from home could find the strength to perform the gruesome task he describes in his memoirs:

In the afternoon I was detailed to wait on the amputating tables at the field hospital. It was a horrible task at first. My duty was to hold the sponge or “cone” of ether to the face of the soldier who was to be operated on, and to stand there and see the surgeons cut and saw legs and arms as if they were cutting up swine or sheep, was an ordeal I never wish to go through again. At intervals, when the pile became large, I was obliged to take a load of legs or arms and place them in a trench near by for burial. I could only stand this one day, and after that I shirked all guard duty.

According to “The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. (1861-65.)“, ether or chloroform or a combination of the two was used in over 80,00 instances. Wounds festered at an alarming rate on the battlefield. Field doctors were forced to use amputation as a means to stop the spread of infection as antibiotics did not exist yet. It was agreed among field surgeons that the introduction of chloroform and ether was indispensable for saving lives. As the use of chloroform or ether was a relatively new concept and was now being used on such a mass scale, it was a matter of trial and error and some deaths were attributed to it’s use.

According to “The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. (1861-65.)“, ether or chloroform or a combination of the two was used in over 80,00 instances. Wounds festered at an alarming rate on the battlefield. Field doctors were forced to use amputation as a means to stop the spread of infection as antibiotics did not exist yet. It was agreed among field surgeons that the introduction of chloroform and ether was indispensable for saving lives. As the use of chloroform or ether was a relatively new concept and was now being used on such a mass scale, it was a matter of trial and error and some deaths were attributed to it’s use.

After this bloody war, thousands of men returned home shell-shocked and permanently disfigured leaving their limbs behind while so many others even less fortunate left their lives.