George Ulmer vs. W.S. Harkins

Today’s soap operas have nothing on 19th century melodrama. On March 14,1877 Lizzie May’s troupe performed a play titled Ben McCulloch or Sartin as Death. It’s a strange title and after a week of research I have found no information about the play except a review from the Acadian Recorder newspaper from March 14,1907.

Ben McCulloch (1811-1862) was an actual person who lived a very colorful life. He was a Texas Ranger, a Sheriff, a good friend to Davy Crockett, a Prospector during the 1849 Gold Rush and finally a Confederate General killed during a Civil War battle in 1862. The play which I believe is based on his life certainly had enough drama to draw from!

According to The Acadian Recorder dated March 14, 1907, 30 years ago the play at The Academy was Ben McCulloch or Sartin as Death. The main character was played by Oliver Dowd Byron making his first appearance in Halifax.

The reviewer writes ” Ben McCulloch is practically one of Buffalo Bill‘s blood and thunder stories dramatized, and from the beginning to end there is no cessation of interest. the lynching mob, the burning swelling, the daring rescue, the villainous plot, the robbery, the state prison, the mad Ben, the churchyard in the storm with it’s premature graves, the attempted murder, the exciting recontre, the touching meeting after long years of wasting sorrow, were the composites of the play. “

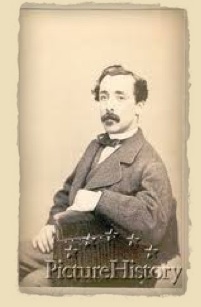

George who fancied himself to be a looker must have been annoyed by the rest of the review regarding a young actor named W.S. Harkins.

“W.S. Harkins is alleged to be the best looking member of the Nannary Company. it has been said that several impressionable young women in the city have fallen in love with him, and that the Academy of Music audiences have been augmented in consequence“.

Sorry George, that’s got to hurt the ego! Lizzie May does not receive a specific mention but as this is a root ’em toot ’em masculine play her role was most likely a small one as damsel in distress or saloon girl.

You decide. Check out the photos of George and W.S. . Who do you think would make the girls swoon?

The Army of the Potomac Paraded Down Pennsylvania Avenue

The Army of the Potomac Paraded Down Pennsylvania Avenue