Imagine the year is 1861. The place is New York City.

A young mother of four wild young boys passes away. The boys’ father Philip, a businessman, decides that the best place for boys is on a farm breathing in the fresh air of the country. He buys land in the interior of Maine and sends the boys up there with a few hired hands to develop the farm. He spends most of his time focused on his work in New York while his boys run wild and free.

A young mother of four wild young boys passes away. The boys’ father Philip, a businessman, decides that the best place for boys is on a farm breathing in the fresh air of the country. He buys land in the interior of Maine and sends the boys up there with a few hired hands to develop the farm. He spends most of his time focused on his work in New York while his boys run wild and free.

Eight months later the boys receive an exciting letter. Their father has re-married, they will now have a new mother to care for them. Even more exciting was the news that they would also have a new little step-sister, only 6 years old. Enter Lizzie May Ulmer.

The following is an excerpt from Adventures and Reminiscences of A Volunteer :

We did not know what day they would arrive. So each day about the time the stage coach from Belfast should pass the corners, we would perch ourselves on the fence in front of the house to watch for it, and when it did come in sight, wonder if the folks were in it; if they were, it would turn at the corners and come toward our house. Day after day passed, and they did not come, and we had kind of forgotten about it. Finally one day while we were all busy burning brush, brother Charlie came rushing towards us shouting, “The stage coach is coming! The stage is coming!” Well, such a scampering for the house! We didn’t have time to wash or fix up, and our appearance would certainly not inspire our city visitors with much paternal pride or affection; we looked like charcoal burners. Our faces, hands and clothes were black and begrimed from the burning brush, but we couldn’t help it; we were obliged to receive and welcome them as we were. I pulled up a handful of grass and tried to wipe my face, but the grass being wet, it left streaks all over it, and I looked more like a bogie man than anything else. We all struggled to brush up and smooth our hair, but it was no use, the stage coach was upon us, the door opened, father jumped out, and as we crowded around him, he looked at us in perfect amazement and with a kind of humiliated expression behind a pleasant fatherly smile he exclaimed, “Well, well, you are a nice dirty looking lot of boys. Lizzie,” addressing his wife and helping her to alight, “This is our family, a little smoky; I can’t tell which is which, so we’ll have to wait till they get their faces washed to introduce them by their names.” But our new mother was equal to the occasion for coming to each of us, and taking our dirty faces in her hands, kissed us, saying at the same time, “Philip, don’t you mind, they are all nice, honest, hard-working boys, and I know I shall like them, even if this country air has turned their skins black.” At this moment a tiny voice called, “Please help me out.” All the boys started with a rush, each eager to embrace the little step-sister. I was there first, and in an instant, in spite of my dirty appearance, she sprang from the coach right into my arms; my brothers struggled to take her from me, but she tightened her little arms about my neck and clung to me as if I was her only protector. I started and ran with her, my brothers in full chase, down the road, over the stone walls, across the field, around the stumps with my prize, the brothers keeping up the chase till we were all completely tired out, and father compelled us to stop and bring the child to the house. Afterward we took our turns at caressing and admiring her; finally we apologized for our behavior and dirty faces, listened to father’s and mother’s congratulations, concluded father’s choice for a wife was a good one, and that our little step-sister was just exactly as we wanted her to be, and the prospect of a bright, new and happy home seemed to be already realized.

We did not know what day they would arrive. So each day about the time the stage coach from Belfast should pass the corners, we would perch ourselves on the fence in front of the house to watch for it, and when it did come in sight, wonder if the folks were in it; if they were, it would turn at the corners and come toward our house. Day after day passed, and they did not come, and we had kind of forgotten about it. Finally one day while we were all busy burning brush, brother Charlie came rushing towards us shouting, “The stage coach is coming! The stage is coming!” Well, such a scampering for the house! We didn’t have time to wash or fix up, and our appearance would certainly not inspire our city visitors with much paternal pride or affection; we looked like charcoal burners. Our faces, hands and clothes were black and begrimed from the burning brush, but we couldn’t help it; we were obliged to receive and welcome them as we were. I pulled up a handful of grass and tried to wipe my face, but the grass being wet, it left streaks all over it, and I looked more like a bogie man than anything else. We all struggled to brush up and smooth our hair, but it was no use, the stage coach was upon us, the door opened, father jumped out, and as we crowded around him, he looked at us in perfect amazement and with a kind of humiliated expression behind a pleasant fatherly smile he exclaimed, “Well, well, you are a nice dirty looking lot of boys. Lizzie,” addressing his wife and helping her to alight, “This is our family, a little smoky; I can’t tell which is which, so we’ll have to wait till they get their faces washed to introduce them by their names.” But our new mother was equal to the occasion for coming to each of us, and taking our dirty faces in her hands, kissed us, saying at the same time, “Philip, don’t you mind, they are all nice, honest, hard-working boys, and I know I shall like them, even if this country air has turned their skins black.” At this moment a tiny voice called, “Please help me out.” All the boys started with a rush, each eager to embrace the little step-sister. I was there first, and in an instant, in spite of my dirty appearance, she sprang from the coach right into my arms; my brothers struggled to take her from me, but she tightened her little arms about my neck and clung to me as if I was her only protector. I started and ran with her, my brothers in full chase, down the road, over the stone walls, across the field, around the stumps with my prize, the brothers keeping up the chase till we were all completely tired out, and father compelled us to stop and bring the child to the house. Afterward we took our turns at caressing and admiring her; finally we apologized for our behavior and dirty faces, listened to father’s and mother’s congratulations, concluded father’s choice for a wife was a good one, and that our little step-sister was just exactly as we wanted her to be, and the prospect of a bright, new and happy home seemed to be already realized.

A home is all right With father and brother, But darker than night Without sister and Mother.

Above: a great photo of George from the George Stewart Collection

Above: a great photo of George from the George Stewart Collection The Army of the Potomac Paraded Down Pennsylvania Avenue

The Army of the Potomac Paraded Down Pennsylvania Avenue

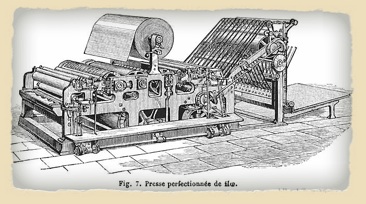

This picture was taken from Dictionnaire encyclopédique Trousset, also known as the Trousset encyclopedia, Paris, 1886 – 1891.

This picture was taken from Dictionnaire encyclopédique Trousset, also known as the Trousset encyclopedia, Paris, 1886 – 1891.